I wrote this short story some years ago for a collaborative book of poetry and photography. I recently came across it again and decided to brush it off and add some AI generated images. (If you are looking at this page on a phone the story comes after the pictures).

The Horse Trough

Although the street ran east to west, parallel to the river, only the south side ever caught the sun. The north side sat in perpetual twilight, except for a few weeks each autumn when the light reached the ancient mulberry tree beside the marble horse trough.

During those brief days, the stagnant water warmed and bloomed green with algae. Sun starved plants in the marble’s cracks burst into flower, drawing glossy hoverflies and honeybees from the waste ground around the crumbling ruin of Bleak House

Those magical days were nearly done now. The mulberry tree stood in mottled shadow, its leaves sheltering a family of sparrows and a pair of magpies from the searing late-summer heat.

Joe leaned out of his attic window, telescope pressed to his eye. He’d made it himself a cardboard tube and a pair of old lenses he’d found near the Broadway, where bombed out shops had spilled their contents into the streets. He suspected the lenses came from the optician’s on the corner of Mill Road.He focused on the inscription carved into the horse trough.

Be kind and merciful to all animals.

“It works,” he murmured, shifting for a better view.

“Don’t lean too far you’ll fall out!” his grandmother called from below.

Startled, Joe jerked back and cracked his head on the window frame.

“Ouch!”

“That’ll teach you,” she said, laughing as she cleared the breakfast plates.

With a sigh, he dismantled the telescope and tucked it into his cupboard. He’d made a little space for it among his other treasures.

The front door creaked open downstairs, and heavy boots climbed three flights.

“Joe… Joe, you up there?”

“Yes,” he called back.

His father’s head appeared at the attic door. “Pop across to Hugget’s and get me some aniseed balls. Four ounces’ll do me till tomorrow night. I’m nearly out of ration coupons.”

His father had quit smoking after he had dropped a cigarette that had burned Joe’s younger brother. Mother hadn’t forgiven him for the accident, though she didn’t mind the extra cash for essentials. Pear drops helped keep the nicotine craving at bay.

“Best avoid Mill Road,” his father added. “Couple of incendiaries hit the engineering works last night. Sounds like some of the men didn’t make it".

Joe didn’t like Mr Hugget. His sweet shop sat a hundred yards away, on the north, shadowed side of the street. Hugget was an unpleasant, joyless little man whose wife had vanished years ago. There’d been a police investigation, and the usual muttering in the pubs, but nothing ever came of it.Most days he stayed in the back room, only slithering into view when the doorbell clanged a grey slug disturbed from its hiding place.

Joe crossed the sunlit cobbles and felt the air cool as he stepped into the north side gloom. The shadows deepened near the shopfront.

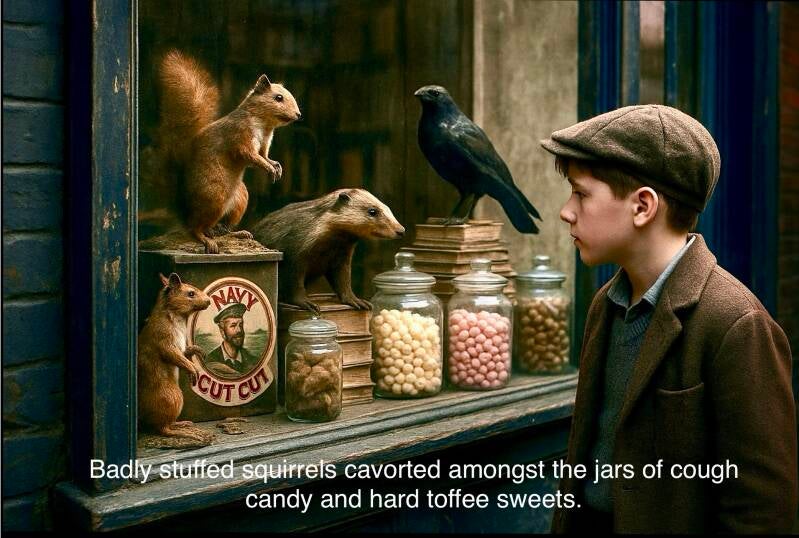

What made Mr Hugget worse was his taxidermy. He filled the window with his handiwork badly stuffed squirrels frozen mid-leap among jars of cough candy, a moth eaten badger sprawled across a Navy Cut cigarette advert, and a dusty crow perched on a stack of yellowing stationery. The crow’s glass eyes always seemed to follow Joe, and now and then, in the shifting light, it almost looked as though it winked. Joe removed his hat as he entered and stuffed it inside his coat.

The bell over the door jingled as Joe stepped inside. Newspapers strung across the ceiling fluttered and tugged at their pegs, like sail boats on a choppy sea. The air reeked of mothballs, liquorice, and disinfectant. A cobwebbed light fitting swayed overhead, casting a sickly yellow glow that barely reached the corners of the shop.

A cough came from behind the penny-drinks dispenser, followed by the slow shuffling of feet.

“Yes, boy?” Hugget emerged into the light.

He was middle-aged and balding, with a brow so large it made his deep-set eyes look like black, wet sockets. “Speak up.”

“A quarter of aniseed balls, please, Mr Hugget.”

The shopkeeper grunted and glanced at the crowded shelves, peering past bottles of bright sweets as though hunting prey. He lurched forward, lifted down a jar, and shook a few pieces into the brass scoop.

“Your father still off the weed?” he asked.

“Yes, sir. Four weeks now.”

“That’s no good to me, boy. More profit in fags than in these bleeding sweets.”

Joe handed over the coins, took the bag, and slipped out as quickly as he could.

The air outside was fresh again. He crossed back towards the south side of the street, pausing to look at the horse trough. Tiny black flies drifted upwards in the warm currents, and a scatter of dandelion seeds turned slowly in the golden light.

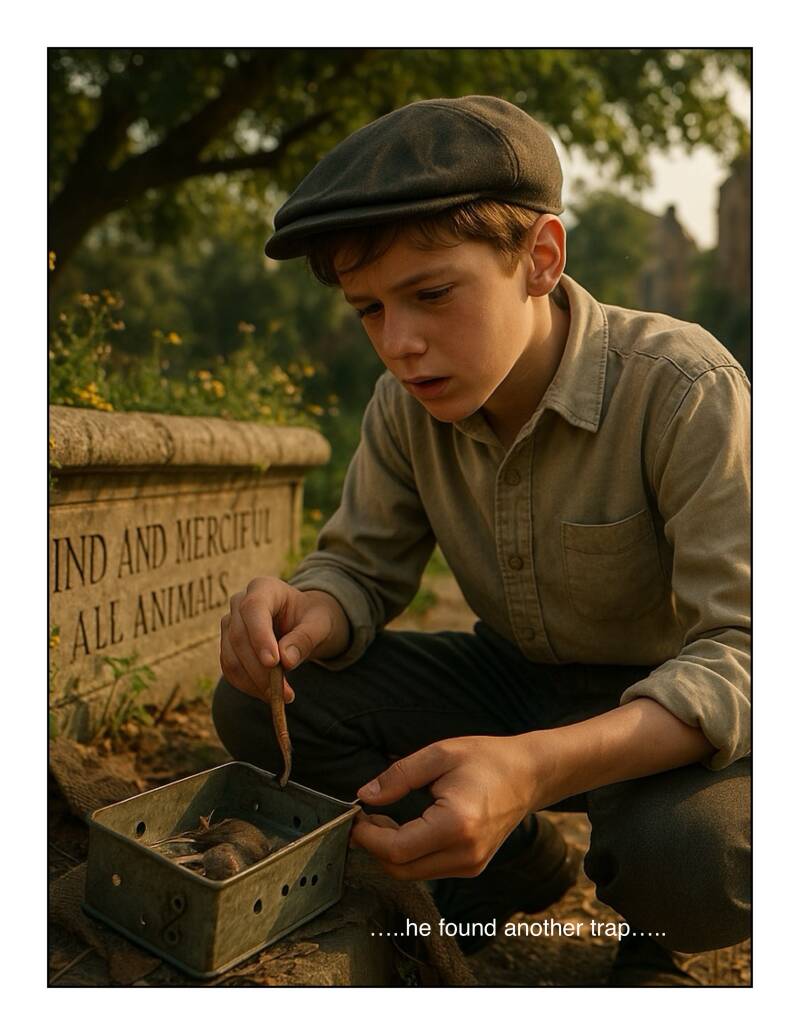

As Joe passed the trough, a metallic glint caught his eye. He stepped closer. Beneath the marble, half-buried in dead leaves and litter, sat a small metal box with a hinged flap punched through with tiny holes. A coiled spring kept the flap tight.

“A trap,” he thought to himself.

Circling round to the back, he spotted a larger one under a sheet of rotting sacking. He snapped a twig from the mulberry tree and prised open the smaller trap. Inside lay two dead field mice.

The larger trap had birds in it. Three starlings one lifeless, the others flapping frantically were crammed inside. As soon as Joe pulled the flap, the living birds shot into the air.

He stood there for a moment, the smell of warm feathers and death clinging to him. Then he gathered the tiny bodies, carried them home, and buried them in a shoebox at the far end of the garden. He said a few quiet words over the mound and covered it with a broken slate.

That evening, he decided to keep it to himself. His family wouldn’t understand they’d only laugh or scold him for making another “animal cemetery.” Better to wait, to watch.

When the sun dropped, he set up his telescope on the windowsill. The light was almost gone, but he managed to focus on the far end of the trough where the traps lay.

Almost immediately there was movement.

A shadow shifted behind the trough. Joe twisted the eyepiece. The figure crouched low, feeling along the underside. With a sudden jerk, it lifted the larger trap, reached in, and pulled out a dead starling. The body went into a canvas bag. The smaller trap followed something small and limp disappearing into the sack.

Then the figure froze. Slowly, it raised its head, nostrils flaring, cocking its head to one side like a strange bird listening to the night.

It stood, and the light caught its face.

Mr Hugget!

Joe almost toppled off his chair. He yanked the telescope away and ducked below the sill. The last thing he wanted was for Hugget to catch him.

The next morning, Joe woke with the decision made he’d tell his parents what he’d seen.But as he left his room, voices floated up from below.

“Mrs Bennet says it’s the strangest thing. No one knows what’s happened,” his gran was saying.

“Have the police been called?” his mother asked.

They were all gathered at the front door, peering down towards Mill Road.

Joe padded down a flight to hear better.

“It’s Hugget,” his father said. “He’s sitting in the shop window right there amongst the stock and the stuffed animals.”

Joe’s pulse quickened. He pushed past them and ran up the street. A crowd had gathered outside the shop, everyone staring through the dusty glass. He edged forward until he could see.

Mr Hugget sat in the centre of the window. Or rather, something wearing Mr Hugget’s skin did.

He was perched on a stack of firework boxes, his watery eyes bulged, fixed on some distant point beyond the crowd. In his hands, he held a jar of aniseed balls, seemingly offering them to the group infront of the shop with a grin that bared too many teeth.

Then Joe saw the wound a ragged gash running from ear to ear, sewn shut with coarse string. Beneath the stitches, straw bulged from the gap. His wrists bore matching slits, also stuffed and tied.

A murmur rippled through the crowd.

“My God… he’s been stuffed,” someone said.

Joe’s gaze wandered to the rest of the display. The badger’s coat shone like polished mahogany. The squirrels seemed to twitch mid leap. Even the old crow, now glossy-feathered and sharp-eyed, looked almost alive. Its gaze met Joe’s.

It winked.

In the years that followed, the horse trough became famous in that part of London. Each August, people came to see the wildflowers, the bees and hoverflies, the sparrows and magpies. Someone suggested fencing it off, making the north side of the street a protected sanctuary. The Mayor came. Even a minor royal stopped by, smiling for the local paper.

Rumours about Mr Hugget never faded. Some said his past had finally caught up with him. Mrs King, who ran the Albion Arms and dabbled in séances, claimed she’d dreamt of a chorus of frogs singing to her: All dues have been paid they told her. The regulars loved that story. Even Polly, the pub parrot, got involved, occasionally screeching “Bugger Hugget!” for no reason at all.

The sweet shop stayed empty for years. When it was demolished in 1973, the workmen found thousands of tiny animal bones in the cellar and one human skeleton, thought to be his wife’s.

Add comment

Comments

Brilliant short film there in the making beautiful